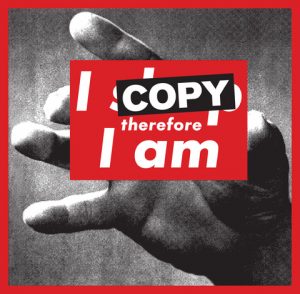

SUPERFLEX I COPY therefore I am 2011. Image courtesy the Superflex Studio, Denmark

Artists have borrowed, sampled, nicked, copied, cut and pasted, adopted, hijacked, referenced, remixed and/or repurposed imagery and ideas from ‘elsewhere’ for centuries, to create their own artworks. Leaving aside the intention to ‘pass off’ as their own images and ideas taken from someone else, when done with creative integrity, appropriation in art offers another way in which to rethink, retell or reassign understandings and meanings of prevailing political, social and/ or historical narratives.

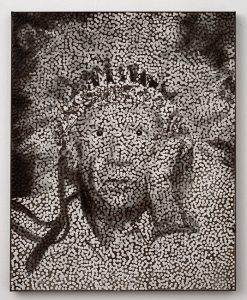

Daniel Boyd Untitled 2013. Oil and glue on canvas. Image courtesy the artist and ArtAND Foundation

The artists in the exhibition CAUGHT STEALING [sic] at the National Art School Gallery (NAS) boldly flaunt the theft of imagery and materials in their recent works. From a very literal perspective, CAUGHT STEALING harks back to the origins of the site on which NAS sits. It was originally Darlinghurst Gaol and where you were incarcerated should you have indeed been ‘caught stealing’! As some of the artists have close connections with NAS the art school, and, given that its Gallery’s exhibition program reflects the School, its teaching principles and its alumni, it makes sense to include works by their artist/ teachers, many of whom are highly regarded practising artists in their own right.

Entry to the National Art School, Darlinghurst. Images courtesy the ABC

National Art School campus aerial view. Image courtesy NAS

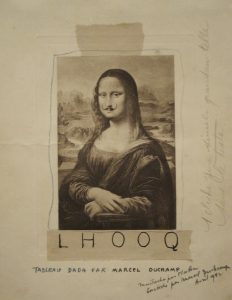

Its timing is perfect, given the master of appropriation Marcel Duchamp is the highlight exhibition The Essential Duchamp at the AGNSW at the moment. Duchamp’s Readymades flipped the norm on its head: objects with little or no meaning beyond their utilitarian guise were taken from their regular contexts, cleaned up, set up and offered up in a gallery space.

Marcel Duchamp Fountain 1917. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz

Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia L.H.O.O.Q, 1919

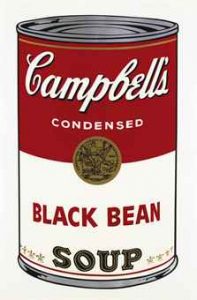

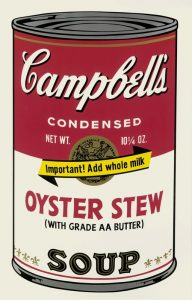

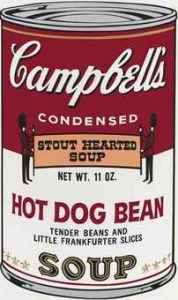

As their recognised identities receded and, given a new title, the ‘readymades’ were repurposed for reconsideration. Duchamp and his fellow Dadists, Surrealists and many subsequent artists of the 20th C (think Warhol for example), took great delight in overtly taking and copying existing images, spinning different concepts, either serious, irrational or hilarious, to reject the prevailing cultural standards and propose a different ‘normal’.

Andy Warhol From the Campbell’s Soups I 1968 screenprint portfolio

CAUGHT STEALING curated by Dr Jaime Tsai presents work by leading Australian artists who have indeed been ‘caught in the act’, re-using images, ideas, materials and techniques as part of their artistic strategy to create works which are provocative, invigorating, thoughtful and ironically – their own.

The exhibition is about challenging and resisting the status quo: activism at its most aesthetically and intellectually beautiful. It is about demanding change for how our history is told, by whom and in what language; greater awareness of environmental issues; embracing diversity and, in case it all feels too PC, upending authority and disregarding the agreed laws of copyright. It is a rollicking, energetic and provocative treat.

Australian art luminaries are well represented – Hany Armanious, Fiona Hall, Louise Paramor, Joan Ross, Destiny Deacon, Gary Warner, Daniel Boyd, Peter Burgess and partners (in crime)Sean Cordeiro and Claire Healy – together with the next rising generation – Lillian O’Neil, PhilJames, Harley Ives and Soda_Jerk – make for an impressive exhibition.

There is good mix of contemporary history in the selection of works. It is refreshing to see older work – from the earlier 2000’s – of leading artists. Some of the more significant works in this exhibition have been tucked away in significant private collections but have been made available for this exhibition. It is an enlightened collector who appreciates the responsibility of their custodianship, and who willingly and generously lends key works to a public institution.

You know a show is going to be satisfying, when the first artworks you encounter are those by two extraordinary artists Fiona Hall and Destiny Deacon. Though they come from very different perspectives, they share an artistic approach which aims to shift our perspectives of authority. Both are dextrous in their technical touch and prowess, Hall in particular. She never ceases to amaze me with her capacity to weave (sometimes literally) meaning, aesthetic, technique and materials together in a way which is compelling and unique.

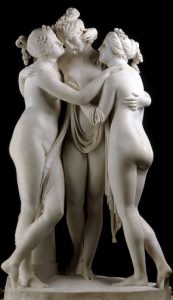

Both Deacon and Hall have borrowed from the art historical cannon, from images and presentation, to lay bare the legacy of colonisation. Deacon’s The Three Disgraces is an arresting about-face on the charm and beauty of the Three Graces idealised in art and myth.

Destiny Deacon

The 3 diss graces, 2009

inkjet print from digital image on paper

60×45cm. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Antonio Canova Rome The Three Graces, 1814-1817, carved marble. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hall presents her finely-crafted beaded objects in a formal museum vitrine, those cabinets in which priceless, much revered treasures, invariably gathered in dubious circumstances to satiate a misguided curiosity, are displayed.

Fiona Hall Understorey, 1999 – 2004. Glass beads, silver wire, plastic. vitrine dims: 176x150x87cm. Private collection, Sydney. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

If you haven’t already been, may I suggest a visit to the Centenary extension of the ANZAC War Memorial in Hyde Park to experience Hall’s deeply moving commemorative offering to those from NSW who have served in the Armed Forces in the 20th and 21st centuries.

For those of us who weren’t in Venice for the 2011 Biennale (or in Melbourne in 2012) and missed Hany Armanious’ major installation in the (previous) Australian Pavilion, you will be thrilled to see this work at NAS – Adzeena Persius, 2010.

Hany Armanious Adzeena Persius 2010. bronze, gold plate, semi precious gemstones. Two installation views at the 2011 Venice Biennale. Private Collection, Sydney

It is ambitious in every way, and loaded with art historical significance, as a commission for a Venice Biennale demands. It is witty, intriguing and glitters, though now sprinkled with dust. It is the type of work that stops you in your tracks and asks of you – ‘why’ and ‘how’? And it isn’t ‘just because’. There is a conceptual rigour and labour-intensive process to his practice which imbues in everyday, inconsequential objects a greater value of a higher order. Armanious’ works ask us to consider how we understand and value the physical, conceptual, social and cultural orders around us.

In Adzeena Persius (2010) nothing is as it seems. Armanious has taken the pretty flimsy, mass-produced school desks (of, maybe, the 70s), together with (I gather) a Burger King cardboard, make-it-yourself crown and given them value well beyond their original insignificance. The desks are cast in bronze and stacked as a precarious tower. The crown is cast in gold-plated silver, with semi-precious gems. Even the dust on the desktops (not cast!) has value: it is dinky-di Venetian dust which, though originally not an intentional finish to the work, is now carefully preserved, anchoring the work to an honoured time and venerated place.

Hany Armanios Adzeena Persius 2010 detail.

Armanious is a sculptor who has consistently maintained his focus on the casting process, during which an original object is used to create another, a replica. It is a highly technical, specialised process which aims at recreating a perfect match. Though it may seem a clone on first glance, Armanious creates something else.

A recent body of work brings the age-old casting technique well into the 21st Century. It is the techno version of ‘replicating’ – scanning. To make this recent series, Armanious photographed the walls of artists’ studios, specifically the bits where paint splattered beyond the canvas onto the studio wall.

Hany Armanious Stereotypes, 2018 eco-solvent vertical surface print on wall 180×500cm. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

It is the leftovers, the seemingly inconsequential, but nonetheless the handiwork of the artist which never reaches the gallery walls, which interests Armanious. He photographs a stray, inadvertent paint spray by a well-regarded artist, scans it, then digitally prints it – just the once – directly on the gallery’s and then, with a bit of luck, the collector’s walls. A subtle but effective commentary on the commodification of art and imagery in the digital age, as well as the limitations of copyright ownership. Is there sufficient ‘artistic merit’ in the splatter over which to claim from the bundle of rights within copyright?

He is the artist-alchemist, turning what has little value into something which is highly prized and sought after, shifting meanings of objects and of perceptions of the hierarchies of power in our consumerist culture.

Louise Paramor is another who takes the every-day, discarded bits and pieces to build wondrous sculptural installations. In CAUGHT STEALING is a detail from an earlier work, Show Court 3. It was first made in 2007 as a temporary large-scale installation presented on the Rod Laver Arena in Melbourne – hence the bright green plinth, reminiscent of the bright green tennis court surface. Brightly coloured, large-scale plastic objects are balanced together, as static anthropomorphic figures, striking sporty poses with a wilful playfulness between them, though there is neither a tennis ball nor no. 1 seed in sight.

Louise Paramor. Show Court 3 2007 detail. Installation view at NAS. Image courtesy the artist

Sean Cordeiro and Claire Healy work together to repurpose everyday items as a comment on contemporary lifestyles – including their own – as they pursue both artistic careers across the globe and manage a young family.

With Venereal Architecture the artistic couple built sculptures of LEGO animals awkwardly entangled in IKEA furniture. Cordeiro and Healy use a lot of LEGO (they also have young children) as their building blocks for a number of significant artworks. LEGO and IKEA have much in common. They are both world-famous, recognisable brands; symbols of domesticity and consumerism, of childhood and adulthood aspiration; designed to be constructed and de-constructed. Both are made from what has only recently been acknowledged as the environmental evils of the 21st century: plastics and wood pulp, sourced from destruction of natural habitats. Delightful to look at and wander around, and important to consider.

Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro

Kitchen / Pantry – Seal, 2014 LEGO IKEA foot stool and plant

103×110×112cm. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro Garage / Tool Shed – Doe, 2014. LEGO IKEA trestle with shelf and plant 130×150×70cm. Image courtesy the artists and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

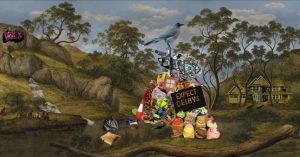

Joan Ross, PhilJames, Gary Warner and Soda_Jerk take the borrowings one step further. The original imagery has its own cultural and corporate significance. These artists take it, keep it and add to or subtract from it, using it as a visual or conceptual platform from which to create something of contemporary relevance.

Gary Warner literally sweeps up the censored celluloid cuttings off the floor before they end up in the bin, and pieces together a narrative which speaks to the shifting histories of society’s moral boundaries and expectations.

Joan Ross plays with Glover and Gainsborough in a witty and biting digital jaunt through a colonial countryside, the paragons of colonial virtue disregarding and disrespective of both Indigenous peoples and environment. As we now know is true.

Joan Ross, Landscaping, still from the video The Claiming of Things, 2012. Single channel video. 7mins 36secs. Image courtesy the artist and Michael Reid Sydney

Joan Ross Expect to merge, still from The Claiming of Things, 2012. Single channel video, 7mins 36sec. Image courtesy the artist and Michael Reid Sydney.

PhilJames uses the backdrop of several reprinted dreary versions Stations of the Cross, adding in recognisable cartoon figures to animate the otherwise weighty religious load.

Philjames Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus 2019 oil on vintage offset lithograph. 120x95cm. Image courtesy the artist and Olsen Gallery, Sydney

Philjames A Game with Time and Infinity 2017 oil on vintage offset lithograph 120x96cm. Image courtesy the artist and Olsen Gallery, Sydney.

Soda_Jerk are represented here by a terrific work – The Was from 2016, It is a collaboration between the sibling duo and the music band, The Avalanches. Described as a “sampledelic trip through the neighbourhoods of collective memory” it is part-experimental film, part-music video and part-concept album devised by two groups of artists who excel at gathering and sampling filmic images and music snippets, to tell a completely different story.

Soda_Jerk & The Avalanches Still from The Was, 2016. Digital video, 13:40mins. Image courtesy the artists.

There is little regard for copyright in this revised film. Soda_Jerk says of copyright law “… that it monopolises ownership and control of representations, narratives and resources of collective culture”. They snip and sample existing images and music to undermine the power structures which insist on ownership of the images and sounds; their work becoming emblematic of resistance and a shift in world order. It is a non-violent hijacking of ideas with little regard for the niceties of copyright attribution, but with an inherent respect for the image itself and its potential for an ‘alt-life’.

Soda_Jerk & The Avalanches Still from The Was, 2016. Digital video, 13:40mins. Image courtesy the artists.

This sibling duo created the film TERRA NULLIUS (2018) enabled by the Ian Potter Moving Image Commission, a major joint initiative between the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) and The Ian Potter Cultural Trust. Controversially the Trust withdrew its support at the time of its launch, citing the work as “unAustralian” – whatever that actually means.

Soda_Jerk Terra Nullius 2018, still. Digital video, 54mins. Commissioned by ACMI.

Soda_Jerk are die-hard believers in open source, shared material so enjoy this video online and make your own decision. (For a terrific, hard-hitting discussion of what it is to be either “Australian” or “unAustralian”, check out Artspace’s recent exhibition Just Not Australian – now closed – on its website in which Terra Nullius featured).

Copyright law may have also been put to the test in Tara Marynowsky’s recent series Coming Attractions 2017-2018 in The National at Carriageworks. Based on a similar approach of snitching, Marynowsky used footage from well-known movies (Pretty Woman, Indecent Proposal) and scratched on the celluloid around the features of the protagonists, frame by frame, to recalibrate the story.

Tara Marynowsky. Still from Pretty Woman, from the series Coming Attractions 2017. Image courtesy the artist, The National and Chalkhorse Gallery, Sydney

It is a timely critique on the reassessment of film culture and the representation of women in it, brought on by the #MeToo movement.

And just while we’re here at The National in Carriageworks and talking about appropriation, I should mention the extraordinary body of work Apókryphos presented by photographer Cherine Fahd. These 9 of 24 B&W photographs document the funeral and burial of her paternal grandfather. The then 2 year old Cherine was not present in the Church nor the cemetery.

Cherine Fahd, from Apokryphos 2019. Digital photographic print. Image courtesy the artist

Cherine Fahd From Apokryphos 2019. Digital photoraphic print. Image courtesy Cherine Fahd

Cherine presents the photographs and, with permission from the key stakeholders – her family – curates a selection, upscales them and annotates them. She makes a dual index, one which is factual identifying people and objects; the other, more emotive and evocative of retold memories around the tragic occasion.

Though the settings and characters seem like something straight out of Fellini or The Soprano’s (and no, I am not suggesting anyone here is a gangster: it is the stereotype adopted by The Soprano’s), they are documentation of real life, and one that is private and rarely presented. Who takes photographs of funerals and burials? The fact that they exist at all warrants a closer, deeper look.

The politics of ownership is not a concept that is central to Cherine’s earlier body of work but it can be woven well into this discussion. No-one in her extended family knows who took the original photographs. Other than her grandmother, the wife of the deceased, no-one can remember them being taken. Her grandmother never discussed them, just handed them to Cherine, the anointed family archivist, in her latter years. They have a professional touch to them, but who this accomplished photographer was, despite efforts to identify them, remains a mystery. With Apókryphos Cherine is reclaiming ownership of the images, on behalf of the people in them, whose story they describe. It is her family’s memories and that history belongs to them.

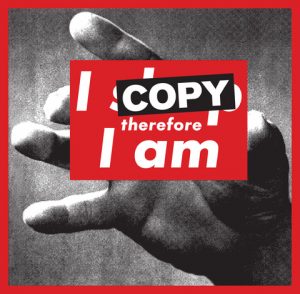

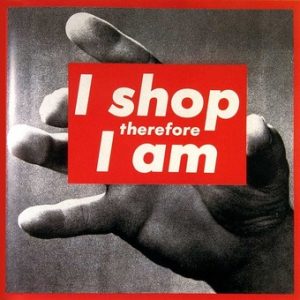

And who can argue with this most potent of images: SUPERFLEX’s image I COPY Therefore I Am. Produced in 2011 it deliberately and unashamedly takes directly from Barbara Kruger’s I Shop Therefore I Am of 1986 (which we saw in Sydney at the 1988 Biennale of Sydney and whose strident message still rings in my ears!).

SUPERFLEX I COPY therefore I am 2011.

Barbara Kruger Untitled (I shop therefore I am)

281x287cm photographic silkscreen/ vinyl

1987.Image courtesy the artist

SUPERFLEX is a Danish-based collective which seeks to challenge the role of the artist in contemporary society and explores the nature of globalisation and systems of power. With the ‘copying’ of this key artwork for their own purposes, SUPERFLEX too shows a deliberate disregard for copyright acknowledgments, taking on an activist mantle and testing their concerns about the political and philosophical concepts of copyright in a digital age where (almost) anything goes with instant sharing, copying and manipulating any image on Instagram, FaceBook, SnapChat and all the filters and tools they provide, to change an original into something else.

So when does appropriation (the act of borrowing) become misappropriation (deliberate fraudulent misuse)? When is copyright infringed? When do artists have the right to appropriate other artists’ work for their own use? There has been much advocacy for artists’ moral rights, in Australia by respected bodies such as The ArtsLaw Centre of Australia and the National Association for the Visual Arts. The Copyright Act enshrines the moral rights of the owner of original material to ensure the work is not borrowed or taken, to be reused, to be ridiculed or demeaned. How does this then sit with artists using and twisting other’s works to take a stand or make a point. Have these artists indeed been ‘caught stealing’? Is it appropriation or misappropriation? Do they have the right to take a crack at the establishment, in way which may be perceived as disrespectful of their fellow artists?

Copyright lasts for the duration of the life of the artist plus 70 years. Joan Ross’ play with Gainsborough and Glover is fine – they’re long gone; same with Philjames. But Soda_Jerk and The Avalanches, and their splicing and dicing of someone else’s images and music? Cherine Fahd with the unclaimed authorship of the original photographs? How do their re-uses of these original works hold up? Is it sufficient to justify this usage as comfortably within their practices and their own moral rights?

The legal discussions could go into the early hours, over many bottles of red, but perhaps one place to start is to consider ‘intent’. Were the artists’ intentions dishonourable or disrespective of the original. Soda_Jerk say that all film and music is a testament to the culture and time in which it was created: their’s is an inherent respect for what previous art forms reveal of earlier generations. Cherine does not claim the original images as her own and is keen to find the original photographer who documented her family’s tragedy. What better way to do that, than to publicly present his or her extraordinary images. It is an unfolding scenario. Maybe Tara Marynowsky and Philjames sought permission for the reuse of images from the Disney and Hollywood powerhouses? Maybe these powerhouses aren’t interested in chasing artists with little financial backing?

SUPERFLEX’s literal and conceptual copy of the Kruger work is only appreciated and understood in the context of the original. The respect for the original, its visual and social impact is a crucial element of their mischievous doctoring. It is arguable the intentions are honourable. In a different age when technology did not so easily facilitate such sharing, Oscar Wilde was heard to say: Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. In this instance I think this wisdom is worth remembering.

CAUGHT STEALING is at the National Art School Gallery until 10 August

2 Comments

Great article Fi. Bring on the lawyers !

Loved your review of Caught Stealing which was nicely spiced with food for thought. It’s said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder – maybe ‘honourable intentions’ are too?